IDRIS KHAN: MEMORIES AND MONUMENTS

Memory is a strange and amazing thing. Sometimes it stores experiences indelibly, engraving them permanently in our minds. Other times it is more like a shadow cast fleetingly over our thoughts. Memory is complex, sometimes profound and honest, other times meaningless or deceptive. It can grow stronger or weaker. It can be what we hold most dear to us, yet it can let us down or desert us entirely. It also lives beyond us as individuals, seeping out into our collective consciousness, sharing the past and shaping the future.

Memory plays a significant role in the practice of internationally acclaimed, Walsall-born contemporary artist Idris Khan. As his major survey exhibition opens at the New Art Gallery Walsall this week, his own memories of growing up and studying in the Black Country town will inevitably be in his thoughts. As an artist who has exhibited everywhere from the British Museum to the National Gallery of Art in Washington and the Espace Culturel Louis Vuitton in Paris, this exhibition is not only a homecoming of sorts, but a celebration of all that he has accomplished since graduating from the Royal College of Art in 2004.

Memory is abstract: our brains storing and recalling tangible things as thoughts. It is a human urge to try to make memories tangible again, to re-give them physical form so that we don’t forget a moment, a place, a person. As a natural repository for memory, it is perhaps no surprise that photography has been such a prominent medium within Khan’s practice. He rapidly rose to prominence with works such as Holy Quran (2004) in which he painstakingly created an image built up of many layers, each one a spread of pages of the holy book of Islam. Beautiful, poetic and powerful, Khan’s work is a testament to the devotion of those who read and follow the Quran. The work speaks of reading and re-reading, of contemplation and reflection, of teaching and learning. It speaks of how many times, and how many people, have read to themselves or read aloud the words of the book, committing parts to memory. It is an abstract work that speaks of faith, belief and language itself.

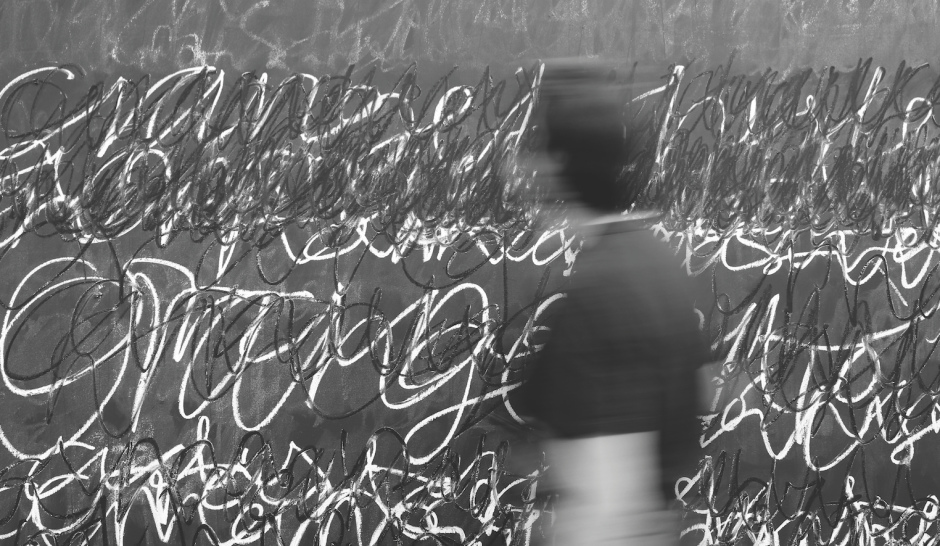

In addition to religious scriptures, Khan has explored many other subjects and themes through this process of photographic layering, from Sigmund Freud’s text on Leonardo da Vinci and the uncanny to the early photography of human and animal motion by Eadweard Muybridge or the industrial structures documented by Bernd and Hilla Becher. Almost always in black and white, often physically imposing and regularly haunting, Khan’s visual palimpsests are equally studies in time, bringing together many hours of thought, many things created, many places visited into one single visual moment, fusing them in space and time. In recent bodies of work he has employed paint, building up marks and lines using oil sticks which he then layers further through photographic processes. From works that are almost pure white to those that are almost entirely black, Khan explores mark making as abstract gesture, with abstract painting itself under the scrutiny of his lens.

A recurring theme in Khan’s oeuvre has been music and sound, explored through the scores of Beethoven, Mozart and Schubert among others. A work such as Black Horizon (2010) turns the notes of Bach into dense abstract marks, almost like waveforms, reverberating with the sounds they depict. It was also through Bach that Khan first ventured into film in his installation A Memory After Bach’s Cello Suites (2006), commissioned by inIVA in London. Here sound was layered in an audio counterpart to the layering of visual imagery through the performance of cellist Gabriella Swallow, her bow moving like a ghostly light against the strings of the instrument, set against a pitch black backdrop.

While this work was ethereal, Khan’s interest in music and musical notation took on a very different, and decidedly heavier, form in a work curiously titled Listening to Glenn Gould’s Version of the Goldberg Variations while thinking about Carl Andre (2010). Again a response to the work of Bach, this time Khan pushed his practice into the domain of sculptural installation, sand-blasting overlaid parts of Bach’s score into thirty dark blue steel panels, presented partly flat on the floor, perpendicular to others on the wall. Just shy of ten metres in length, it is an imposing, monumental work that brought together his enquiries into music with the history of modernist, minimalist sculpture (Carl Andre being a hugely influential and once controversial figure in post-war minimalist sculpture).

Khan’s journey towards monumental minimalism took an even larger step forward with the work Seven Times (2010), a large-scale floor installation comprising 144 blue-black steel cubes. Each cube has the proportions of the Kaaba, the sacred black, gold and white structure located inside the Grand Mosque in Mecca that is considered the centre of the Muslim world and around which pilgrims are required to walk seven times. The footprint of Khan’s installation is the same as that of the Kaaba, and each of the artist’s cubes is inscribed with prayers in Arabic that are recited daily by Muslims. Presented in low lighting, Khan’s installation is a memorable and affecting monument to prayer and pilgrimage.

While Khan’s sculptural works have previously had monumental qualities, a major project by the artist unveiled last November is actually a monument, following a commission from the United Arab Emirates to make a memorial in Abu Dhabi to honour the nation’s fallen heroes. Opened in the new Memorial Park next to the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque on the nation’s Commemoration Day, Khan’s large-scale monument takes the form of a series of cast aluminium tablets, each supporting the next. The minimal tablets convey both a sense of those who have fallen and those left standing, with an underlying sense of the strength that comes from supporting one another when facing adversity and war. Khan’s abstract, minimalist practice has taken on the form of a large-scale memorial for remembrance, a monument for memory.

Matt Price